A Pinewood Derby Life Lesson

My Pinewood Derby racer was a thing of beauty. In fact it was so perfect no one believed I had built it. A ten year old simply didn’t have the skills to build such a car. What they didn’t understand is I had patience learned from two intelligent and perfectionist parents and an artistic talent, no doubt inherited from my mother.

It was 1963. I was a Cub Scout in the fifth grade at Gatewood school. Every year our Cub pack sponsored a Pinewood Derby, in my opinion the only interesting thing Cub Scouts were allowed to do. Most of the rest of it seemed like grade school arts & crafts at some other kid’s house while cub mothers supervised. I would rather have been out galavanting around the neighborhood or through the woods with my buddies. I think I made it through two years of Cubs before I bailed. In that time I only built one Pinewood Derby, but boy was it cool.

Every kid started with the same derby car kit in a cardboard box – a block of pine with a crude square cutout where the cockpit was supposed to be, four 6d finish nails for axels, hard plastic wheels and two wood axel struts. Like me, the Pinewood Derby was only ten years old. It was the brainchild of Don Murphy, a Cub dad and model builder who was trying to find something his son could do that was akin to the Soap Box Derby. The model building part of him took over. They say over 50 million kids have participated in Pinewood Derby’s since, so some of you have probably experienced the satisfaction of building and the excitement of racing such a car.

Building a car like this was a natural extension of my little hobby of building plastic model car kits. I would save my allowance and regularly buy them at the local Seattle Sporting Goods store. Because I was already building models, I knew how to paint, glue and assemble parts. The exciting part of a Pinewood racer was two-fold: it was a race car I could actually race, and it was something I could essentially build from scratch. Right away, I started looking at race cars of the day, trying to model my racer after them. My dad was a do-it-yourselfer, so he had all the tools I needed. He showed me how to use the power tools to cut the basic shape I had drawn on the top and sides. There were hours of whittling, sanding and shaping to get the rear fin and the curves just right on both sides. I still remember how exciting it was to see my car taking the shape of a Sterling Moss Formula 1 car.

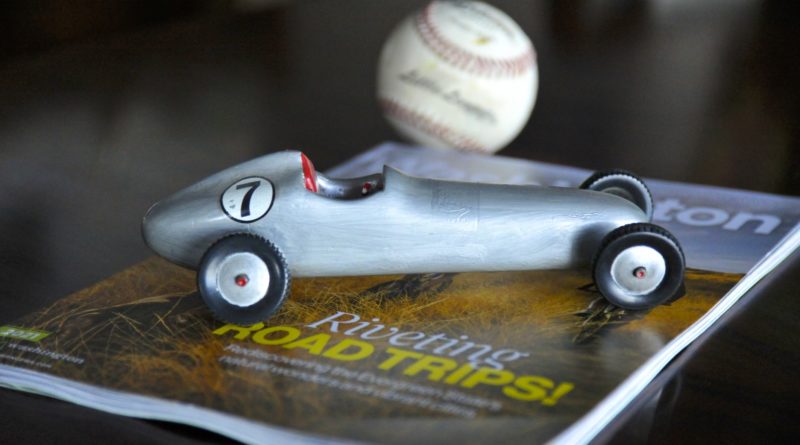

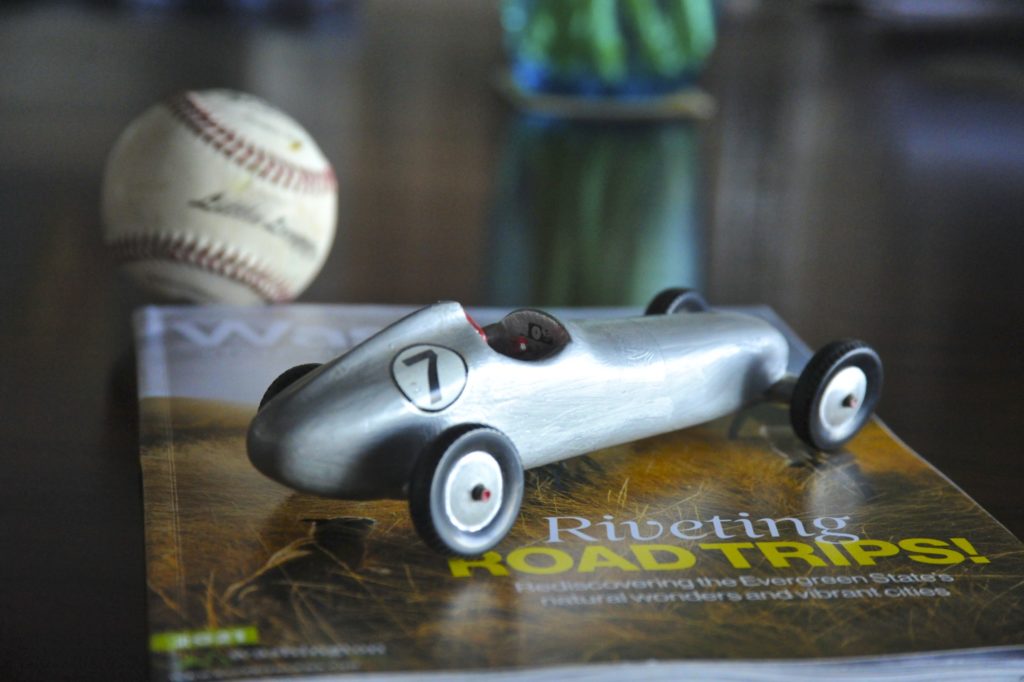

I used wood glue to bond on the struts, added the wheels and nail axels with more glue and wood filler, and shaped the cockpit with left over pieces of pine, bonding them into place and blending them with more filler. Then there was still more sanding. Finally ready for paint, Dad told me I needed to seal the wood, so I put on a primer. Silver seemed like a fast color, so I hand brushed 4 coats on it. I painted the wheel centers silver to look like real tires on wheels and even dabbed red paint on the nail heads to emulate center wheel hubs. We greased the wheel hubs on the nail axels with graphite. I tried to trim them so they wobbled as little as possible.

I always saved parts and decals from my plastic models, so I scrounged through my scraps and found some racing numbers, a steering wheel and an instrument panel decal. I had carved a seat into the cockpit, so I painted it red, installed the matching red steering wheel with a 4d nail and put on the decals. You can still see the remnant of a rectangular decal across the hood just ahead of the cockpit that didn’t survive the years. I want to say it was the Mobil Pegasus flying horse, but I don’t really remember. The ‘7’ numbers just happen to tribute my favorite historical driver, Sir Sterling Moss (Much later, although I never thought of it when I bought them, my racing shoes also have Sterling’s #7 emblazoned on them).

About the only marginally legal thing my dad did was take the car to his lab at Boeing where he poured molten lead into a hollowed out space in the undercarriage so the car was as close to the legal 5 oz weight limit as possible. That was the one thing I didn’t do.

On race day I dressed in my Cub uniform for Pack 284 and up to school we went. There were at least a hundred people in the auditorium where the track had been erected. This was a big deal for a 10-year old. I don’t know if they still do this, but back then they had an award for the best looking car. My car was so cool looking and so much more real looking than any other car there. The judges thought it was too much better, that my dad must have done most of the work. They pulled him aside and quizzed him. Unconvinced, they pulled me aside and asked me. I was stunned. You doubt I built this?! I thought. Are you going to disqualify me because I did too good a job? Don’t you understand? I was building a piece of art!

I wanted to prove you could have a car that was fast and beautiful. I thought those things should Always go hand in hand. And I still do. It’s why I own an Aston Martin and not a Lamborghini or even a Ferrari.

I remember telling them the only thing my dad had done was put the melted lead into the bottom of the car and shown me how to use the power tools. They looked at each other, some doubt still displaying on their faces. They went away and discussed it. In the end, they let my car race. It easily won the best looking car and came in second overall, losing to a low, black wedge racer. The plaster award plaques and ribbons didn’t survive the years, but the memory and the great feeling of accomplishment and vindication still do.

The steering wheel has broken off now, and the wheels wobble badly on broken plastic hubs. An axel is held in place by an old green rubber band that looks like its about to disintegrate. The decals are chipped and not all of them survived. But the timeless shape, the iconic fin and those wonderfully curved surfaces live on. I don’t see how, even today, I could have done a better job.