Gentleman, Racer, Hero

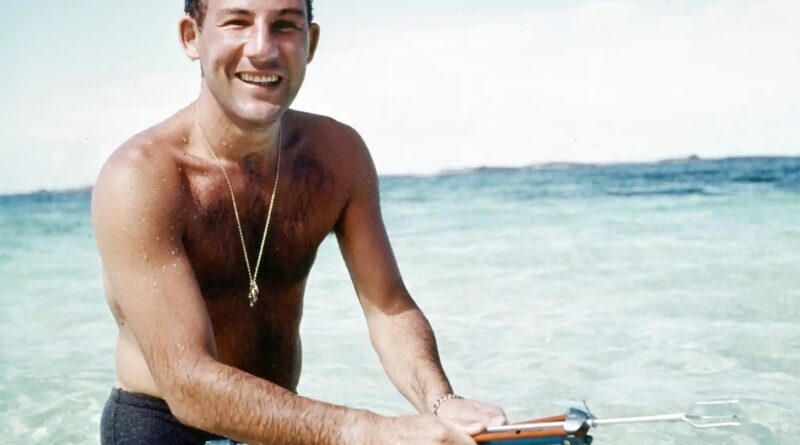

There was a magic about this man. His handsome and stylish demeanor was made all the more so when combined with his thoughtful, almost shy, unassuming manner. Yet he brimmed with an assured confidence. No braggadocio, no bravado, or boisterousness; he was all the best that defined class. He lived a fantasy life as a man dancing between exhilaration and death, between courage and fear. He was a racer of cars. He was not, as he explained, a driver. He was a racer. To him, that was a difference as large as night and day.

Sterling Moss was one of my childhood heroes. Funny thing, he still is. When I was eleven I built a pinewood derby racer. I modeled it after a Sterling Moss race car. I painted it silver and put his favorite number 7 on it. When I found the car years later, I suddenly remembered how intentional the number 7 was. He is a man who will live forever as, to my mind and those of many others, the greatest race driver of all time. To him, racing was poetry in motion or, maybe more appropriately, the motion of poetry. He was always relaxed, laid back and silky smooth, appearing as if he was enjoying every moment. He made the art of racing look simple and effortless. In warm weather he often raced in short sleeves. He always drove, by racing standards, in a somewhat reclined position while sporting a stylish, white equestrian helmet. Class all the way; that was Sterling.

Where other drivers considered themselves on the edge of control, at 10/10ths so the saying goes, Moss would easily surpass them, often by seconds in a single lap. A second in racing at that level is an eternity. He is commonly known as the greatest driver to never win a Formula One Season World Championship. I think that sells him well short. He is, quite simply, the greatest driver to ever live. Many drivers who watched him, competed against him and were teammates with him felt the same.

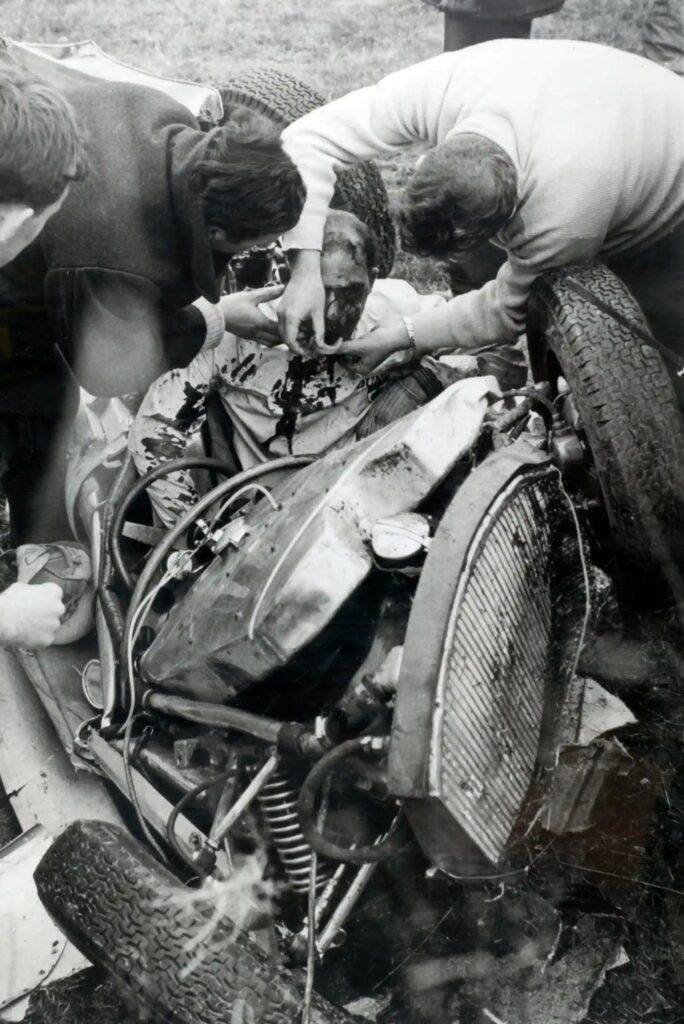

Born in 1929, he was active as a racer between 1948 and 1962. He proved immediately to be a natural, and could have competed at least another ten years had not a terrible accident derailed him. He was in a coma for 38 days, with the right side of his brain separated from his skull, his left eye socket and cheekbone crushed, with multiple broken bones up and down his left side. He finally made it back into a race car a year later with a test drive of a Lotus 19 at the very track he had crashed trying to avoid unforeseen circumstances while overtaking another car. The test was pretty routine, and to Sterling that was the problem. As Robert Edwards, in Sterling Moss, the Authorised Biography, relates, “He realized, with a dawning sense of horror… All the flowing instincts, the unthinking balancing, unbalancing and rebalancing of the car, all those things which the Maseratis had taught him, were absent. To the uninformed observer, the performance was probably impressive; to Sterling himself it lacked everything which he had come to love about the sport and his place in it. Gone too was the schoolboyish enthusiasm for the sheer, fierce joy of it. If his relationship with a racing car had once been a sensuous dance, it was now more like a vaguely recalled hop with a mere acquaintance. There was no flow. It was a disjointed, disconnecting experience; thoroughly depressing.”

“…Sterling finally realized that this was life in the real world; this was what it was like for everyone else and that the massive advantages that he had unconsciously enjoyed for so long were now a thing of the past, alien to him and probably impossible to recover. He was now as other men.”

How does one recover from a realization like that? Racing was the only thing he had done in his young life. He had only held one other job as a teen, and that didn’t go to spectacularly well. There were two things, however, he hadn’t counted on. Early on, his father had cleverly insured his racing career and formed a company protecting Sterling’s financial interests and commercial viability. Endorsements and appearance contracts remained intact. Second, Sterling seriously underestimated his public appeal. Something, I suppose, only a truly modest man would do.

Left – At Goodwood in 1962, Moss is worked on in the wreckage of his Lotus. It took them 45 minutes to extract him.

In Britian, he was considered something of a national treasure, and certainly one of national pride. Perhaps, surprisingly, his fame and image only continued to grow over time. But knowing what I do of the man, in the final analysis this is not at all shocking. His non-plussed demeanor and cool detachment in fielding, analyzing and formulating answers to questions about his professional and personal lives was endearing and admirable. He felt no shame for anything he had or had not done, other than always wondering if he might have done more to aid other drivers, even in the heat of battle. You won’t find that in today’s race drivers.

His ability to openly reflect and consider every question about life and his place it, about his racing, and invariably about the women who surrounded him was forthright, unpretentious and honest. It’s hard not to build tremendous respect for a man who goes about his business honorably, without appearing defensive or secretive. He was a breath of fresh, clean air. I believe he was everything he appeared to be, and what he appeared to be was extraordinary. Both on the track and away from it, he was the same good man.

He didn’t care for today’s racing, where drivers use cars as weapons to either show their disapproval of another’s on-track conduct, or to shunt someone off because they let their goals be momentarily overridden by their tempers. In general, drivers are control freaks anyway, but when you add a large dose of narcissism to the mix it becomes anything but the kind of racing Sterling lived for – the kind that relied strictly on skill and the good sense of other drivers so you could be alive for the next race.

There were consequences if you ran into someone. Today, cars are so safe there’s typically little chance of serious injury. That is wonderful, but it also creates a driver mentality that there is no ultimate risk to ‘taking someone out’ if the mood strikes you. Sportsmanship, so important to Moss, is just a shadow of what it once was. His was an era of adventure, honor, huge risk and a corresponding need for mutual respect. He found no joy in racing the way drivers do today. Let your skills show the man you are. Own up when you aren’t good enough. Salute the man who has outdone you. Do the right thing. Stop when help is needed. Life is more important than a victory.

There was no finer racer. He was a gentleman to the last, a man who accepted his fate with grace and a gratitude for simply being alive. I will always want to remember him that way. The way we always want to remember our heroes.

BRAVO!

A great tribute to fantastic gentleman. We will not see his like again.