Invention, Innovation & The Pace of Adoption

Predictions rarely take into account the variables of widespread adoption. And man’s ability to adapt hasn’t changed much.

The story of the cell phone brings to mind the pace of invention, innovation and social adoption. Futurists always have an unwavering optimism about the adoption of new technologies. In 2017, the experts told us autonomous vehicles would begin dominating the landscape in five to ten years. They also said we would have Jetson-style flying cars in ten years, robots would take over manufacturing in the next few years, and on and on.

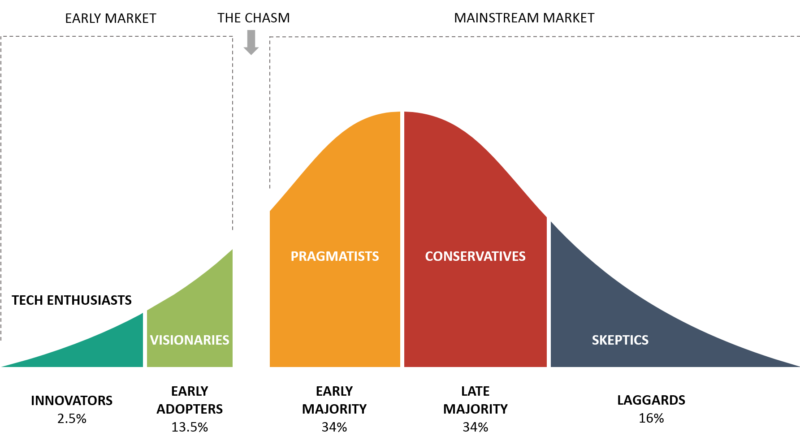

My natural skepticism requires me to take a step back and consider a few facts. For starters, invention is one thing, but technological adoption and social acceptance are quite another. Human nature can only accept a certain rate of change to remain comfortable. People don’t want to be in such a constant state of change that there is no continuity. I would also venture to say that to the bell curve above there is a correlation between social age groups. Younger people will tend towards the left side, while older people will tend towards the right side. Add to that the economic complication that older people tend to have more disposable income, which is often used to try out new things.

Second, existing infrastructure and economic development do not easily allow wholesale abandonment of existing technologies. A return on investment must be met both economically and socially before we can move on to new things.

Third, any potential social and ethical questions posed by new inventions and technologies must also be resolved. All these things conspire together to more or less define a set timeline for the adoption of new technologies. I have come to realize that cycle is about thirty years.

Some people believe this cycle can be compressed as we become more technologically advanced. I disagree, because it is not a technological problem. It is a social, moral, psychological and economic problem. I don’t include political and regulatory variables because they are not historically consistent and can be loosely grouped with any of the other components. To prove my point I looked at a few examples to help understand and illustrate this invention/adoption cycle:

The telegraph was invented in the 1830s, but wasn’t commonly used until the 1860s.

The telephone was invented in the 1870s, but wasn’t commonly adopted until the 1900s.

The automobile was invented in the 1870s, but wasn’t commonly seen until the 1900s.

The television was invented in the 1920s, but wasn’t commonly used until the 1950s.

The electronic computer, invented in the 1940s, became relatively common in the 1970s.

The internet, invented in the late 1960s, wasn’t commonly adopted until the late 1990s.

The cell phone is an interesting one. While 1947 research proved cell phones could work, the FCC essentially blocked practical commercial adoption until the 1960s. But it still took until the 1990s before they were commonly in use.

It’s also interesting to note different industries have different mixes of influence between the social, moral, psychological and economic issues. Medical inventions, for instance, usually have huge social, moral and ethical components, to say nothing of the regulatory issues. Also, keep in mind the 30-year timeframe is not a strict number, but generally speaking the time between invention and common adoption falls within a 28 – 32 year window. To further clarify, I also assume a technology becomes common when it is economically viable enough to be reasonably affordable for a significant number of people. I am not the only one who has realized this correlation. I figure if I have thought of it, someone else surely has as well. Geoffrey Moore is an organizational theorist who defined it in a much more technical way in his 1991 book, Crossing the Chasm. This is where the bell curve shown above originated.

It’s important, though, to also make a distinction between invention and innovation because while the pace of the number of inventions may be increasing, the innovation and adoption of each invention is not. And, when it comes to innovation, it’s surprising how many simple ideas with real commercial value are never acted upon, or can’t make the leap across the 16% adoption chasm in Moore’s definition of the ‘early adopters’ to the ‘early majority.’

So, no matter what all the optimists think, the chasm is real and the pace of adoption is set by human limitations. Those limitations are not just psychological; they include physical and economic forces, particularly when there is existing infrastructure to displace or new infrastructure to build. So don’t get too excited about seeing self-driving cars everywhere in the next five years; it’s not going to happen. Having been in the highly federally regulated aerospace industry for 40 years, I can tell you the federal government is going to take a long, hard look at the safety of those cars before they hit the road in great numbers. Add to that the complexity of having car brains that can emulate human brains for adaptive actions to quickly changing, unpredictable conditions and I think we have a ways to go. As a point of illustration, in the case of an imminent collision, which computer will decide his passengers can or cannot be saved? It will be a predictive decision based upon actuarial statistical analysis, not the ultimate preservation of human life. A chilling thought.