The Jazz Age Rat Pack

If you’re not British or a car enthusiast, you’ve probably never heard of them. But if you’re intrigued by adventures of courage and daring, then these boys should be on your reading list. The Bentley Boys were the roaring twenties’ Jazz Age version of the Hollywood Rat Pack. That sums this group up about as well as I can imagine.

I first became enamored with the escapades of the Bentley Boys several years ago when conversing with Bentley owner Walter Carrel at an all-British car show near Seattle (See 1926 Bentley 6-1/2 Liter “Woolfe” Speed Six). Little did I know how amazing this group of young men were. Born along with the Bentley Motor Company in 1919, the Boys’ flame burned brightly for twelve enterprising years. That there is, a hundred years later, much interest in their dashing, heroic undertakings is testament to the nobility of their aspirations, the height of their accomplishments – and the notoriety of their paint the town lifestyles. These were, after all, a largely well-to-do group of survivors from the horrors of The Great War (WWI). After navigating the dangers of that time, they had little compunction to merely return to a desk and while away their remaining years in safe, secure vocations. Living life to the fullest became their sworn duty and bound them to burst headlong into lives their friends, classmates, and family members had been deprived of living out. They had survived for a reason, and they intended to reward that reason with trailblazing purpose. War heroes, noblemen, aviators, inventors, race car drivers, submariners, doctors, journalists, boxers, cricket and tennis players, land and water speed record holders, racehorse jockeys, industrialists, partiers, playboys, defiers of death – those were the Bentley Boys. They lived life on the edge, making headlines just as often off the racetrack as on it.

The Bentley Boys consisted of WWI fighter pilot Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin, Captain Woolf “Babe” Barnato, Lt. Commander Glen Kidston, Frank Clement, Captain John Duff, Dr. J.D. Benjafield, auto journalist SCH “Sammy” Davis, Richard Watmey, “Uncle” Bertie Kensington Moir, Clive and Jack Dunfee, Dale Bourne, George Duller, Dudley Froy, Baron Andre d’Erlanger, Clive Gallop, Bernard Rubin, Joe Brown, Sir Alex Moore, and Jean Chassagne. Of course, there were others involved, too, like Dorothy Paget and AFC Hillstead. They were not just Brits, and many of them were not involved for the full life of Bentley Motors. One was Canadian, one Australian, one even French. Founder Walter Owen (W.O.) Bentley only ever hired one professional race car driver, that being Frank Clement. All the others raced for the love, danger and challenge of it.

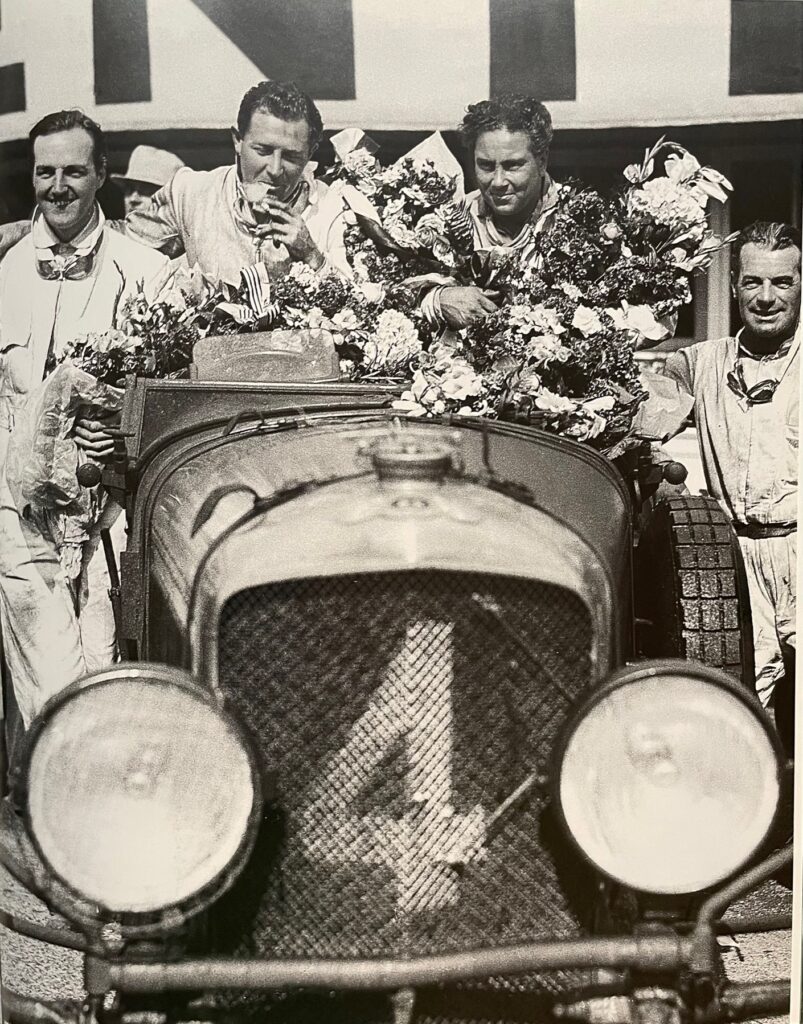

In its brief twelve year history, the Bentley Motor Company won The 24 Hours of LeMans 5 times in 7 years, including 4 in a row from 1927 to 1930. On the way to victory in 1929, Bentley Boys took the first four places. Eight of the Boys could claim victory at LeMans: Woolf Barnato, Tim Birkin, Dudley Benjafield, Sammy Davis, John Duff, Frank Clement, Glen Kidston and Bernard Rubin. They were a close-knit group. Four of the Boys had apartments around Grosvenor Square, carrying on parties for days that were the talk of legend. As they often parked their Bentleys at the southeast corner of the square, it came to be known as “Bentley Corner.”

John Duff, the first Bentley Boy and the first Bentley winner of LeMans along with Frank Clement, was actually a Canadian born in China. When WWI broke out he made his way to England and enlisted. After the war he opened a Bentley dealership, heard of this 24 hour race at LeMan and decided to enter his own car. He and Clement were 4th that first year of 1923, convincing WO Bentley to support their efforts the following year when they won. His racing career ended when he broke both ankles after going over the banking at Brooklands racetrack. However, he took up fencing, went to Hollywood and became a fencing and eventual all-around stuntman. Returning to England several years later, he proceeded to become a champion show jumper and died in a horse riding accident in 1962 at the age of 67.

Most of them ranged from well-to-do to fabulously wealthy. Still, this was an eclectic group with all the trappings fame, fortune, chivalry, heroism and patriotic duty could muster and intertwine. Possibly the wealthiest and most famous of the group was Woolf Barnato. Babe, as he was known, inherited interests in the deBeers Diamond consortium and Kimberley Diamond mines, both of which his father, who came from nothing, founded. He was immensely wealthy with none of the inhibitions of old money or nobility. Had F. Scott Fitzgerald known of him (it’s possible he did), then F. Scott’s main character in The Great Gatsby could well have been Barnato. The parties at his 1,000 acre estate, Ardenrun, were legendary. Ardenrun was the 1920s version of the Playboy Mansion and the Great Gatsby, all rolled into one. Movie stars, celebrities, royalty and the well-heeled all played there. In a time when the annual wage of an average bloke was about 100 pounds, Barnato would frivol through 800 pounds a week. If that ratio would hold today for an average Londoner making 42,000 GBP a year, Barnato would be burning up around 350,000 GBP ($435,000) on incredible weekly parties that would last through the night. No excess was too much.

And yet, despite his womanizing and bon vivant lifestyle, he was also an astute businessman, generous philanthropist, and sportsman. Handsome and powerfully built, Babe was a championship cricket player, prizefighting boxer, scratch golfer, accomplished tennis player, champion raceboat driver, and still today the only racecar driver ever to win the 24 Hours of LeMans 3 times in 3 tries. If there was one thing he respected more in a man than his money, it was his athletic prowess. Barnato ended up bailing out Bentley Motor Company from receivership in 1928, becoming its Chairman and simultaneously it’s best racecar driver. After losing close to 100,000 GBP on Bentley, Barnato sold out to Rolls Royce in 1931, unceremoniously making founder W.O. Bentley a mere employee of Rolls Royce. Barnato was married three times, had two daughters and two sons. He passed away in 1948 from complications after an operation for cancer. He was 52.

Barnato’s co-driver for the 1928 LeMans victory was Australian Barnard Rubin. Rubin had also served in The Great War, where he was so seriously wounded it took three years of treatment before he could walk again. Rubin, also an airplane record-setter and racer, became close friends with Barnato, even living with him for a time. Rubin died of tuberculosis in 1936, aged 39.

Like Barnato, Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin also benefitted from family wealth gained from his father’s prominent lace manufacturing business. Birkin, like most of the Bentley Boys a survivor of the atrocities of WWI, was committed to honoring his homeland with heroic feats gained through racing. Speed records and race victories, especially against foreigners, were his constant goal. With his blue and white polka dot scarf flying behind him, he was by all accounts the fastest driver of the group, but also the most daring and reckless, being hardest on the race equipment. He set several speed records at the famous Brooklands racetrack, lapping at nearly 140mph in 1932. Distinctly different, Barnato seemed to possess a sixth sense about the level of performance he could squeeze from a car and still finish. Birkin was a contrast of traits. A well-known ladies’ man, he also was a bit self-conscious of his shorter stature and possessed a noticeable stutter. Yet, he was a confident and fearless driver. Birkin met an untimely death from blood poisoning after burning himself on the exhaust pipe of his Alfa Romeo and not getting it properly treated in time. He was only 37.

Like all the Bentley Boys, Dr. J.D. Benjafield was also an intriguing character. As a bacteriologist, he was instrumental in controlling malaria outbreaks in the British army during WWI with innovative techniques. He later developed the first successful vaccines against the 1919 Spanish flu. His methodology for creating those vaccines were still being referenced in medical papers more than 60 years later. Despite a very successful medical practice, Benjy’s real money came from his wife. He became a Bentley Boy almost on a whim, when he ended up purchasing a sporting Bentley after accepting a dare to tour the Brooklands race track with salesman/Bentley Boy Kensington Moir. The doctor had dared to insinuate Bentleys weren’t fast enough, upon which Moir challenged him. Still in shock after the 120 MPH tour of the track, Benjafield meekly said yes to the purchase as much to save face as anything. But after a few months with the car, he was hooked. Moir noticed his potential and Bentley brought him on as a racer. The good doctor went on to race for several years after Bentley was bought out by Rolls Royce in 1931, and he continued his successful practice until passing away at the age of 69.

Not to be outdone, however, was the man with nine lives, Glen Kidston. Wealthy from the family shipyard business, Kidston was a sportsman of field games, who also enjoyed big game hunting, motorcycle and auto racing, sports fishing, and boxing, as well as being an accomplished airplane pilot. Barnato characterized him as “…the beau ideal of a sportsman. The word fear had been expunged from his dictionary …a man about town when in the mood, a man of action in another.”

Like most of the Boys he was also a staunch patriot. Kidston’s real distinction was his uncanny knack for survival, as he literally was a cat of nine lives. During WWI he escaped not one, but three warship torpedo sinkings on the same day – the HMS Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue. Also during The Great War, he survived being trapped in the world’s largest submarine as it was stuck on the bottom of the ocean floor in the North Sea.

Depending on how you’re counting, lives 5 and 6 were exchanged in Africa when he managed to shoot a charging wounded lion before it got to him and then separately downed a charging wounded rhino from a mere six feet. For life number 7 he walked away from an auto racing crash in the Ulster Tourist Trophy race at over 95 mph. If you’re not impressed with this one, remember these were the days of open cars with no seat belts or roll bars.

His eighth life may have been his most impressive – surviving a commercial airplane crash. Shortly after takeoff he sensed a crash was imminent and managed to brace for the accident. Trapped in the burning wreckage, he kicked and clawed his way through a fracture in the fuselage while being consumed by fire. Putting himself out by rolling about in the grass, he re-entered the plane and managed to save his co-passenger, the badly burned Prince Eugen von Schaumberg-Lippe. Also badly burned, Kidston nevertheless proceeded to fight his way a mile through woods at night to summon help. He ended up being the only survivor, but spent several weeks wrapped like a mummy recovering from his burns.

He finally ran out of lives in another airplane crash, this one only days after setting a record flying from England to Cape Town, South Africa averaging over 130 mph. While in South Africa, on a whim he decided to borrow a DeHavilland Puss Moth and tour the country. The plane reportedly broke up mid-air during a sandstorm. He was identified only by his name in a shirt collar and a signet ring gifted by his wife. Glen Kidston was only 32.

If you haven’t begun to notice by now, these men ended up mostly sharing a disturbing lack of lifespan. Seemingly, that’s what happens when you continue living life on the edge. Still, it’s difficult to fault them for wanting the most out of life after having all served with distinction, if not heroically, in World War I. They were not going to be cheated out of a moment of living what time they had left, that was for certain.

Sammy Davis was the exception to the general rule of Bentley Boy longevity, living to the ripe old age of 94. A top British motor racing journalist and graphic artist, Sammy was also an accomplished racecar driver for Aston Martin, Bentley, Sunbeam, Alvis and others. With Aston he helped establish 32 world and class speed records and, with Benjafield, won LeMans in 1927. His greatest claim to fame may have been surviving the legendary crash that year at White House Corner that would claim 7 cars. He somehow managed to continue on and drive the seriously crippled “Old Number 7” to victory. So extraordinary was that finish, it was later celebrated in London at the Savoy Hotel with WO Bentley, the Boys, and other important guests. Old Number 7 even had a place in the room, holding court as the centerpiece of the white tie dinner.

These men set an example of living life as an adventure in every respect. There were dozens of race victories, risky business ventures, outrageous parties, playboy antics, chasing wealthy women (who generally wanted to be caught), foreign adventures, athletic endeavors of all kinds, and crusades set upon to glorify the homeland. High speed and high risk. Adrenalin. The threat of knowing danger was lurking didn’t matter to them. In fact, it was welcomed. It meant life was being lived to its fullest, that envelopes were being pushed and opened. Though they treated it as their duty, they enjoyed every single minute of being in the moment. They epitomized what taking the bull by the horns really means. It must have been an absolutely grand, fantastic life, even if the flame was often snuffed out too soon. It was truly epic. I’d love to see a well-done movie on this group.

There are many books still available about the Bentley Boys. “The Bentley Era,” by Nicholas Foulkes and “Racing in the Dark,” by Peter Grimsdale are two of the more entertaining reads. Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin wrote a memoir, “Full Throttle,” which happens to have been adapted to film. AFC Hillstead wrote, “Those Bentley Days” from the perspective of assisting WO Bentley with the startup of Bentley Motors, and Elizabeth Nagle wrote “The Other Bentley Boys” about the mechanics who built the cars and supported the racing.

Photos are copyright of the WO Bentley Memorial Foundation and LAT Photographic.