To the Summit

A little over 36 years ago fellow ski patroller Chris Chandler and his mate, Cherie Bremer-Kemp, took on the world’s third tallest mountain, deadly Kanchenjunga. They were both experienced high altitude climbers. It didn’t matter.

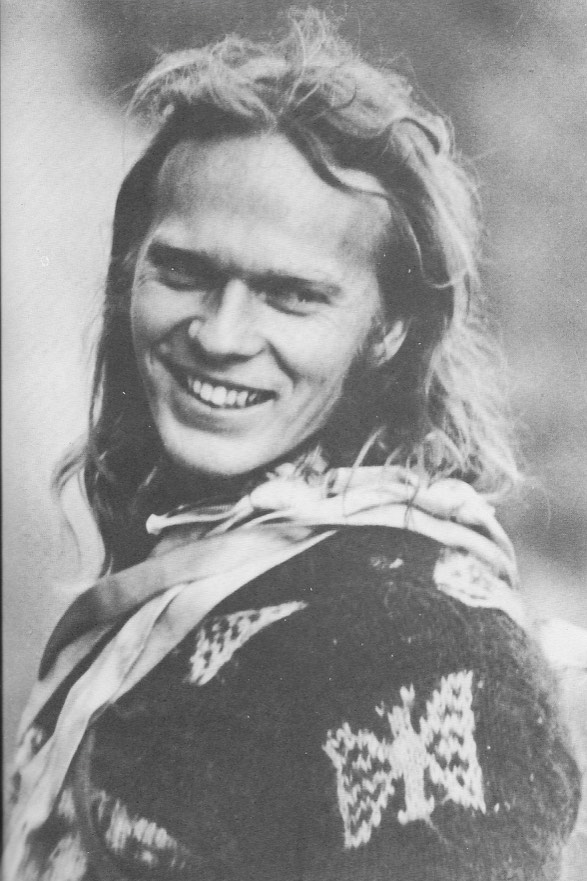

Chris was personable and outgoing with long, blonde hair and California beach boy good looks. And he was brilliant. He graduated from medical school and became an ER doctor. Nimble-minded, quick on his feet, confident, he had the perfect mentality for handling life-and-death trauma. He also had an inexplicable desire to challenge himself, his very existence, against nature. He was an expert skier, an experienced high seas yachtsman, and veteran high altitude mountain climber. He was one of those guys you felt could literally do anything.

As a ski patroller, we would occasionally ski together. He was always up to something, always looking for some way to spice up the day with little challenges. He wasn’t the kind of guy to taunt or openly provoke. He was just looking to test himself, to find the exhilaration of experience. If you wanted to come along, the more the merrier. Four years older than me, I remember him as a lot of fun and a bit crazy when it came to taking risks. He was always ready to take on the world. Mountain climbing, then, seemed like a natural extension of his propensities.

He was never just any man. He was a larger-than-life kind of human being. That he is not as famous as other climbers is an indication of his sometimes quiet, self-effacing modesty and his contemplative wonder of nature. He had a good, strong ego, make no mistake about that; no high altitude climber does not. It’s a prerequisite for choosing to do any death defying act. It’s a balance between unwavering self-belief and the recognition of that thin line between recklessness, the edge, and death. What are you humanly capable of, and how close are you to the edge? In mountain climbing, the edge isn’t just mental, it has very real physical limits. It is the ultimate man against nature. The way Chris liked to experience it, it was also the ultimate self-imposed isolation against existence.

He climbed with the likes of Rick Ridgeway, Jim Whitaker, Jim Wickwire and many of the world’s most accomplished and famous mountaineers. As part of those parties, he sometimes summited when they did not. That was the nature of large team mountain climbing; it was a team and anyone who summited was everyone’s success. Chris climbed the highest peaks in the Himalayas, the Andes, Alaska, British Columbia and our local Cascades.

Of an ascent on the north ridge of Chinchey in the Cordillera Blanca Range in Peru, Ridgeway offered the following description of their final climb in the American Alpine Journal (Vol 19, Issue 1, 1974): “The ridge went quickly but proved exciting where corniced over the west slope. The east side dropped off quickly onto the face and was covered by about five inches of soft powder over hard ice. To the right was the cornice and to the left the threat of an avalanche. We split the difference and trudged up the fracture line, ready to jump in either direction depending on whether the slab went or the cornice. Neither happened and a little after noon we found ourselves on the summit.”

Misjudge and you’re dead. Too slow to recognize the fracture line and you’re dead. Set a wrong foot on the line and jump the wrong way and you’re dead. As Yoda famously said there are no maybes – “Do or do not do. There is no try.” Live or die – nothing in between.

Chris and Cherie made two attempts to conquer Kanchanjunga, the first in 1982, the second three years later. The first time they were sabotaged both by weather and unscrupulous locals they had hired to coordinate and supervise the sherpas, their food and equipment. They learned, and for their second attempt they were more vigilant and better organized along with having better people, including another American nurse whom they made their Base Camp manager.

Their second expedition to climb Kanchenjunga in winter had never been attempted before. It wasn’t their first choice, but in the international politics of mountain climbing, you take what you are given. The winter weather wasn’t so much impeded by snow, as one might expect, but by winds and cold. With 125 mph winds and temperatures as much as -75º F., it was near impossible to move or stay warm. The winds were insistent and devastating. Tents swirled, tore, were repaired, and praying often accompanied the hope they wouldn’t shred entirely. Cherie wrote the book “Living on the Edge” to commemorate that climb. In it she describes the wind as “a constant roar, terrifying in its simple persistence. Sometimes I imagine I’m standing in a dark tunnel, waiting the approach of a freight train from which there is no escape…. Surviving in such a wind seemed out of the question; here we were playing a game with a deadly companion.”

Thirty-four days at over 18,500 feet does things to you, and few of them are good.

Base Camp was established on November 28. Camp 1 at 18,500 feet was finished on December 1. Weather finally cooperated somewhat and on January 14 they began an assault on the summit. Late in the day, Cherie became exhausted and very dehydrated so they bivouacked for the night at about 26,000 feet after digging a small crescent-shaped tunnel for the two of them and their porter companion, Mongol. The next morning, January 15, was to be their final 2,000 foot push to the summit. Getting ready that morning, however, the wind blew the flame out of two stoves used to heat snow into drinking water, and Chris didn’t notice it. Trading propane fumes for oxygen at that altitude can be deadly, and almost immediately Chris began exhibiting symptoms of cerebral edema. While the two are not necessarily related, it was a turning point. Cherie, being a nurse and a climber, recognized his edema symptoms almost instantly. They had no warning signs, but even then, it was too late.

They attempted to move their party down the mountain to at least 24,000 feet, but Chris was too erratic for them to handle. Fighting all day to get Chris down the mountain, darkness finally halted their progress and they had to bivouac again. Chris continued to deteriorate.

Cherie later wrote, “His finely sculptured features, gaunt from weeks of grueling work, had relaxed into an expression of bliss. All the tension and cares of mortal beings had dissolved, there was only peace and beauty shining forth… I bent down to kiss his lips. They were strangely lifeless….”

“As death and love met, my whole being was filled with terror, I felt him letting go of the past and all that we had shared, yet the future had not arrived…. As I lay there looking into a bottomless pit, I was drawn closer and closer to the edge. I was suspended in space, I wanted to go with Chris, to seek out where he had gone… lying there beside Chris I was being drawn into that tunnel, towards the journey I had turned my back on.”

Cherie thought of other things. Like the ominous dream of this very scenario Base Camp manager and fellow nurse, Lori, had related to her before they left San Francisco: “There are three people on the mountain, one person is sitting by himself underneath some rocks while the other two are climbing down alone.”

Cherie “lay there examining the fine tapestry that life weaves, looking at the design that brought Chris and my colored threads together, to blend into the overall pattern. I marveled at the way the individual stitches fit together so neatly to create such a thing of beauty.”

Morning came. She and Mongol made their way back down to Chris, propped him up to “sit where he was, in dignity, with his pack and ice axe beside him, gazing out over the vast Tibetan plateau.” For four days they struggled back to Base Camp, only making it because they were found along the way in the darkness by their liaison officer, Bharat, who had ventured up to find them.

We do not ultimately know what motivates people to greatness, but we do know self-possession is a prerequisite to it, or the attempt of it; a single-minded passion making all else at best a secondary pleasure. The obsession makes all who love the haunted secondary to it, and thereby any love in return is more often than not a sporadic and seemingly insincere distraction. But, as Robert Schoene, MD, commented, “…we dare bravely because we must, for without the burden of dreams there is nothing for which to live.”

A friend wrote this of Chris after his passing. His description of Chris is just how I remember him:

“All the clichés applied to Chris—he was physically strong, psychologically tough, and dedicated to the solitude of high mountains. But the clichés do not begin to define the extraordinary human being who died on Kanchenjunga in January. Other words more readily come to mind—enigmatic, complex, hedonistic, moody, irresponsible—above all, free-spirited. Those are the qualities we remember, molding a personality that was truly unique.

When we joined the Club in 1973, his record was not much different than the other climbers entered on the first page of “Cs” in the AAC News—Phil Cardon, Bruce Carson, and R.D. Caughron. It included impressive winter first ascents in the Cascades, a climb of McKinley, and a number of peaks in Canada. But in the next decade Chris set his distinctive course. First came Peru, and then the Himalaya where he made his mark as one of America’s most accomplished, and least heralded, climbers. Just as he wanted it. He summited Everest in 1976 (the second U.S. expedition to that peak), participated in the successful assault of K2 in 1978, and twice attempted Kanchenjunga in the 1980s. The conventional achievements—impressive as they were to his friends—were not the important thing to Chris. He was the quintessential non-conformist. He didn’t care much about rules. But he was steadfast when he was needed, loyal when it counted.

On Everest he made a lot of sick people well on our way to the mountain. He saved a Sherpa’s life at Base Camp. And then he climbed the peak. As we prepared for the climb I would not have picked Chris as among the more reliable members of the group. It didn’t take long for me to revise my assessment. I quickly realized that despite his somewhat unusual appearance, he actually did what he was asked to do. I learned more about his character when he led us up Liberty Ridge and over the Rainier summit in a whiteout (rescuing some lost Rainier guides in the process). He knew where he was going; and he went there.

That was Chris. He created a world that he wanted, and he lived in it. I suspect Kangchenjunga was the perfect embodiment of that world—Chris and Cherie, alone—challenging God knows what, pushing themselves to the edge, and beyond. Chris would never stop.

He was an obsessed man, and chose to isolate himself in a separate universe. His life, his views, and his actions were a challenge to all of us who knew him. America has lost a distinguished mountaineer, although Chris wouldn’t give a damn about that. We will miss a good friend.”

– Philip Trimble, American Bicentennial Everest Expedition Leader. American Alpine Journal, 1985.

Chris left behind a lover, an ex-wife and two daughters. I’m sure, looking over the Nepalese Himalayas in his last moments, he was thinking of them. When I heard of his passing, I remember thinking, “God, what a waste to lose someone so talented, so special, so alive.”

I am reminded more often these days about Ernest Hemingway’s observation of sport and challenge of the self: “Three are only three sports – mountain climbing, auto racing and bull fighting. The rest are merely games.”

– All quotes not otherwise attributed are from “Living On The Edge,” by Cherie Bremer-Kemp. Mead & Beckett, Sydney, Australia, 1987.